Happy Easter to those of you who might celebrate this occasion. Here are some quick notes on Easter to increase our historical literacy:

Easter is also known as Pascha (Greek: Πάσχα), a transliteration of the Aramaic pascha (פַּסְחָא), from the Hebrew word for Passover, pesach (פָּסַח). Catholics and Protestants generally refer to it as Easter, while Orthodox Christians call it Pascha.

2. We are not really sure where the word ‘Easter’ comes from. See the entry from Britannica:

The English word Easter, which parallels the German word Ostern, is of uncertain origin. One view, expounded by the Venerable Bede in the 8th century, was that it derived from Eostre, or Eostrae, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring and fertility. This view presumes—as does the view associating the origin of Christmas on December 25 with pagan celebrations of the winter solstice—that Christians appropriated pagan names and holidays for their highest festivals. Given the determination with which Christians combated all forms of paganism (the belief in multiple deities), this appears a rather dubious presumption. There is now widespread consensus that the word derives from the Christian designation of Easter week as in albis, a Latin phrase that was understood as the plural of alba (“dawn”) and became eostarum in Old High German, the precursor of the modern German and English term. The Latin and Greek Pascha (“Passover”) provides the root for Pâques, the French word for Easter.

There is a long history of dispute concerning the proper date for observing the celebration, known as the Paschal Controversies. This year, Easter is one week prior to Pascha. It may seem bizarre to us modern folks why there was so much concern over calendars back in olden times, but suffice it to say that calendars were (and still are, but to a lesser degree) very tied up with identities and the ancients payed much closer attention to the rhythms of the heavens and their significance than we do. How many constellations can you point out in the night sky? (Spoiler alert: the Big Dipper is technically only an asterism inside the constellation Ursa Major)

Easter has a long history going back to at least the 2nd century, but likely was celebrated from the very beginning by devout Christians.

Last Supper fresco from Kremikovtsi Monastery, Bulgaria, 16th century AD For many Christians, the forty days leading up to Easter is a time for observing Lent, which corresponds with the forty days of fasting and wilderness withdrawal that Jesus undertook in Matthew 4. Observing Christians will undertake a prolonged fast or withdrawal from a personal pleasure, such as abstaining from eating any meat. Almsgiving and increased penance and prayer are also common. It is a period of what Eastern Orthodox Christians call χαρμολύπη (kharmolúpē), or ‘bright sadness,’ or simultaneous feelings of joy and grief.

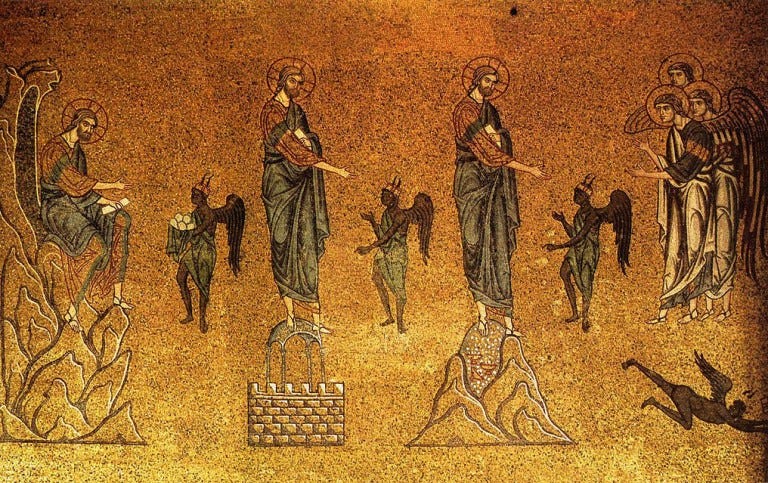

The Three Temptations of Christ. Venice, San Marco, 12c. south vault mosaic in nave crossing. Photograph Wikimedia Commons. 6. The origin of Easter eggs is uncertain. A couple of possibilities are that a) they originated from pagan celebrations of spring because eggs are an obvious symbol of fertility, or b) because of Lent they could not eat any animal products and therefore hard-boiled their eggs and saved them for distribution once Easter arrived.

Hand made traditional hand painted Easter eggs (Polish: Pisanki) and baskets on display for sale on Krakow's Easter market.NurPhoto—NurPhoto via Getty Images 7. There are many traditions around the world for Holy Week, the week leading up to Easter. See here for some examples. In the Philippines, among other places, it is common for Holy Week to include parades of men self-flagellating in the streets in imitation of the suffering of Christ. From what I witnessed there, it was often a case of cutting open the back with razors and then beating it with bamboo sticks attached to ropes to get the blood flowing. If you stand too close to the road you might get splattered with blood. The Philippines is also known for crucifixion reenactments. See for example (if you want), Ruben Enaje, who has been nailed to a cross thirty-three times. This year he prayed for eradication of COVID and an end to the Russian war in Ukraine while on the cross. The motivation for being crucified is most often a desire to imitate Christ mixed with some sort of significant life event, miraculous saving, or loved one in need of healing (and maybe the prospect of becoming a local celebrity) that drives them to undertake such an extreme form of public penance.